Something Like a Cult

What We Hide in Plain Sight and Punish Others for Seeing

I. The Shape of Belief

There is something seductive about a world that makes perfect sense. A world with clear answers, consistent rules and a reliable explanation for every shadow. This kind of coherence is soothing. It draws us in. It offers relief from ambiguity, from the unease of not knowing, from the strange loneliness that comes when reality no longer fits the shape we were told to expect.

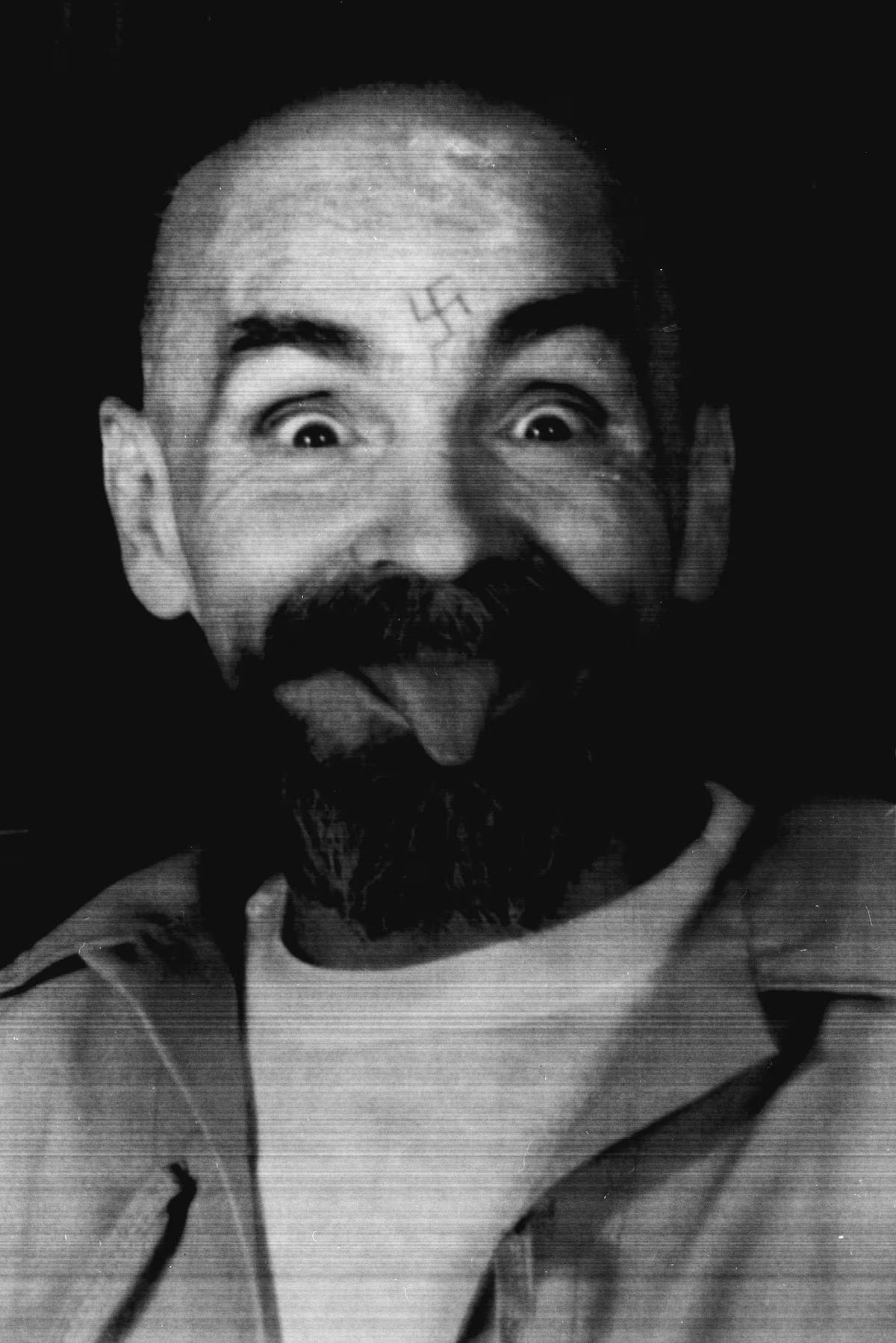

Cults are often described as outliers, irrational pockets of belief, fuelled by charismatic delusion or mass psychosis. But when I read about them, I don’t see aberrations. I see patterns. I see systems that promise safety in exchange for surrender, meaning in exchange for obedience. I see structures that reward certainty and punish doubt, that explain everything and allow for nothing.

The further I follow these stories, from sprawling cover-ups to spiritual empires, from clandestine abuse to tax-exempt orthodoxy, the less confident I feel that these are fringe anomalies. They don’t feel separate from the world. They feel like exaggerated reflections of it.

We like to think we would know the difference. That we would sense the manipulation. That the language would feel off. But what if it doesn’t? What if the logic is familiar, not because it’s rare, but because it’s everywhere?

There’s a reason cults so often begin with a kind of comfort. Not the comfort of bliss, but of order. A story that makes sense of the chaos. A structure that explains what others refuse to acknowledge. It feels like awakening. But in time, it narrows. And what begins as revelation becomes recursion. You are not just inside the system. You are inside its story of why you must stay.

II. Cult Logic and the Question of Legitimacy

Cults are easy to identify when they are small, strange, and collapsing. We see the end-point - the bunker, the robe, the paranoia - and we mistake it for the essence. But cult logic does not always come dressed in prophecy or disarray. Sometimes it wears a suit. Sometimes it buys real estate. Sometimes it wins tax exemptions and writes press releases and builds celebrity outreach programs. And sometimes, no matter how many former members speak out, it remains perfectly legal.

Scientology is one of the most studied and well-documented examples of this paradox. To many outsiders, it is a system of belief with clear cult-like traits: coercion, surveillance, psychological control, financial exploitation and an internal cosmology that isolates believers from the outside world. And yet, it operates in full view. It has buildings, lawyers, PR firms and lobbyists. It sues critics. It owns media. It files paperwork. It plays by the rules of a system that seems designed not to ask whether harm is happening, but whether it is happening legally.

What makes a cult a cult? Is it the belief, or the structure? Is it the secrecy, or the social cost of leaving? Or is it simply whether someone powerful decides it is unacceptable?

Because once you remove the language of fringe extremity, the underlying architecture is hard to ignore. A clear hierarchy of power. A moral framework that renders outsiders dangerous. A worldview that reinterprets all doubt as weakness, all critique as attack. A system of surveillance that masquerades as care. An internal vocabulary that repels scrutiny. These patterns are not unique. They are transferable.

Which raises a deeper, and more uncomfortable question. If a system can exhibit these traits and still function with legal protection, institutional endorsement and public neutrality, what else around us might qualify but escape the label?

We think of cults as tightly bounded, high-drama ruptures in an otherwise rational world. But what if that’s exactly the mythology that allows the rest to continue unnoticed? What if the most dangerous systems are not those that hide in secret, but those that no longer need to?

III. Hidden Systems and the Management of Outrage

There is a category of story that breaks something in the listener the moment it is believed. Not because the facts are too hard to grasp, but because the implications are. Stories like the ones found in Chaos, The Franklin Cover-Up or The Ultimate Evil do not just challenge our sense of safety. They challenge the integrity of the systems we’re told are protecting us.

Each of these books asks questions that refuse to resolve neatly. They do not just explore isolated crimes, but patterns - of silence, of disappearance, of buried evidence and official contradiction. They trace faint outlines of networks that blur the line between fringe and institution, between predator and protector. They hint at power that does not operate by mistake or excess, but by design.

Most people don’t want these stories to be true. And that’s understandable. If they are, then the systems we depend on - law enforcement, media, government - are not just flawed, but compromised. If they are, then harm is not a failure of oversight, but a consequence of structure. The centre does not hold. It hides.

But here is what matters most. The moment someone begins to take these stories seriously, something strange happens. The scrutiny does not fall on the system being questioned. It falls on the questioner. To entertain the possibility that these networks might exist is often enough to be dismissed, discredited or pathologised.

This is a different kind of power. The power not only to erase information, but to erase credibility. The idea becomes unspeakable not because it is disproven, but because it is unpermitted. And the person who refuses to look away is cast as paranoid, delusional, unstable. The belief itself becomes the crime.

There is no clearer sign of a cult system than one that protects itself through reversal: where trust in authority is rewarded and inquiry is punished. Where coherence is manufactured through silence. Where discomfort is reframed as irrationality.

These stories do not ask for certainty. They ask for discomfort. They ask us to sit with the possibility that what we see is not all that is there. And that the most disturbing truths are not always hidden in darkness - sometimes, they are hidden in plain sight, beneath a narrative too neat to be questioned.

IV. The Cult of Sanity

Every system has its boundary markers. For cults, it's the language of insiders and the exile of apostates. For the public sphere, it’s the line between what counts as “serious discourse” and what is dismissed as delusion. But the difference is not as wide as we’d like to think. Because when it comes to protecting dominant narratives, the tactics are often the same: isolate, discredit, delegitimise.

The term “conspiracy theorist” does not function as a descriptor. It functions as a wall. It signals to others that someone is no longer to be taken seriously, that their questions are a symptom rather than an inquiry. The label carries its own moral gravity, not just “you are wrong,” but “you are no longer credible.” And once that credibility is stripped, the system does not need to answer the question. It only needs to signal that the question should not be asked.

This is not about whether a specific theory is true, it is about the architecture that surrounds the conversation. Who is allowed to speak, how evidence is framed and what emotional tone is permitted in the pursuit of truth. Questions about JFK, Epstein, 9/11 or the boundaries of COVID policy are rarely met with curiosity. They are met with derision, condescension or anxiety. The discomfort is not just about the content. It’s about the threat to the order of things.

And so the loop tightens. The more earnestly someone investigates, the more suspicious they appear. The more detail they offer, the more they are framed as obsessive. To resist the label is to confirm it. To ask for clarity is to be accused of fog.

This is how narrative control works in open societies. Not through brute force, but through emotional calibration. Through the soft power of reputational risk. Through the shared, unstated agreement about what kind of doubt is respectable and what kind is dangerous. Sanity becomes its own performance, a way of staying inside the bounds of the speakable.

It is easy to see how cults enforce belief. What is harder to see is how a culture enforces disbelief. Not by suppressing data, but by mocking the frame through which the data might matter.

And if that sounds familiar, it should. Because when a system punishes curiosity and rewards compliance, when it rewrites doubt as deviance, when it uses ridicule to preserve coherence, it has already adopted the logic of the thing it claims to oppose.

V. Seeing Without Certainty

There is no clean conclusion to a piece like this. The point is not to prove something beyond doubt, or to deliver a revelation in full. It is to notice the shape of things, the echoes across systems we are taught to see as separate. Cults, conspiracies, governments, belief structures. Some operate in secrecy, others in plain sight, but many share a logic that rewards conformity and isolates dissent.

The real question is not which stories are true. It’s how we’ve been taught to decide what truth is allowed to look like.

There is power in frameworks that claim to explain everything. There is comfort in knowing where the borders are, who the bad actors are, when the line was crossed. But some of the most important truths arrive uninvited. They are partial, ambiguous, emotionally disruptive. They don’t resolve. They don’t obey. And often, they come disguised as something we were told not to touch.

If the systems we live inside are increasingly recursive, always responding to themselves, closing the loop faster and tighter, then our work is not to escape them entirely. It is to stay awake inside them. To notice when the language starts to narrow. To pay attention when doubt becomes shame. To wonder, gently, what purpose a given label might be serving.

This is not a call to believe everything. It is a call to stay with the questions that make belief uncomfortable.

Because what matters most may not be what we believe, but how we behave when certainty is unavailable. Whether we retreat into prescribed answers. Whether we lash out in fear. Or whether we learn to look, with clarity and care, into the uncomfortable middle.

Some truths are not hidden. They are simply inconvenient. And some systems do not demand belief. They demand that we stop asking.